- Various Artists

-

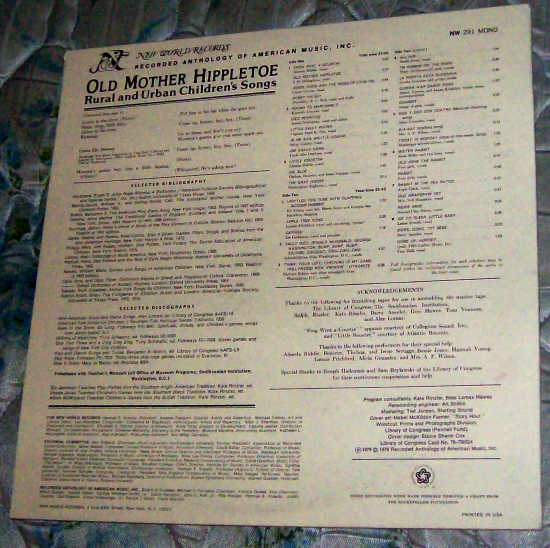

Old Mother Hippletoe: Rural and Urban Children's Songs

Old Mother Hippletoe: Rural and Urban Children's Songs

- Frog Went A-courtin' - Almeda Riddle (vocal) Time: 2:11

- Old Mother Hippletoe - J.D. Dillingham (vocal) Time: 1:43

- Robin Hood and The Peddler (child 132) - Carrie Grover (vocal) Time: 2:09

- Bobby Halsey - (probably) E.C. Ball (vocal and fiddle) Time: 1:47

- Round To Mary Anne's - Kenneth Atwood (vocal) Time: 2:24

- Diez Perritos - Arseno Rodrigues (vocal and guitar) Time: 1:28

- Little Sally Water - Captain Pearl R. Nye (vocal) Time: 1:45

- Je Me Suis Mis-T-A Courir - Sabry Guidry (vocal) Time: 1:13

- Jim Crack Corn [aka Johnny Cracked Corn] - Uncle Alec Dunform (vocal) Time: 1:06

- Little Rooster - Almeda Riddle (vocal) Time: 1:27

- Oh, Blue - Thelma, Beatrice, and Irene Scruggs (vocals) Time: 1:20

- The Gray Goose - Washington (Lightnin') (vocal) Time: 2:32

- Untitled Fife Tune With Clapping Accompaniment - Ed Young (cane Fife); Bessie Jones and Georgia Sea Islander (clapping) Time: 1:13

- Apple Tree Song - Lonnie Pitchford (vocal and one-string ''guitar'') Time: 1:50

- Catfish - Joe Patterson (vocal and panpipe) Time: 1:02

- Sally Died - Schoolchildren from Washington, D.C. (vocals) Time: 0:30

- Ronald McDonald - Schoolchildren from Washington, D.C. (vocals) Time: 0:30

- George Washington - Schoolchildren from Washington, D.C. (vocals) Time: 0:17

- Bump, Bump, Bump [Bop, Bop, Bop At The Doorway] - Schoolchildren from Washington, D.C. (vocals) Time: 0:15

- Salome (was a dancer) [aka Miss Suzy] - Schoolchildren from Washington, D.C. (vocals) Time: 0:10

- Zoodiac [zodiac] - Schoolchildren from Washington, D.C. (vocals) Time: 0:42

- Zing-zing-zing [Related To Name Something Drinking Game On Red Dwarf] - Schoolchildren from Washington, D.C. (vocals) Time: 0:49

- Think - Barbara Borum and Other Schoolgirls from Washington, D.C. Time: 0:34

- Your Left [Has a Big Fat Man from Tennesse] - Barbara Borum and Other Schoolgirls from Washington, D.C. Time: 0:27

- Cheering Is My Game - Barbara Borum and Other Schoolgirls from Washington, D.C. Time: 0:22

- Hollywood Now Swingin' / Dynomite - Barbara Borum and Other Schoolgirls from Washington, D.C. Time: 0:33

- All Hid [All Head] - Bessie Jones (vocal) Time: 1:22

- I'm Runnin' On The River - Three 12-13-Year-Old Girls (vocals) Time: 0:23

- La Puerta Esta Quebrada - Govita Gonzales and Group (vocals) Time: 0:24

- Ojibwa War Dance Song - Albert, Vernon, And James Kingbird (vocals); Time: 0:53

- Chariot - Group Of Girls (vocals) Time: 0:37

- Dos Y Dos Son Cuatro (Mexican Counting Song) - Alicia Gonzales (vocal) Time: 0:20

- B-A-Bay (Spelling Song) - Mrs. A.P. Wilson (vocal) Time: 0:16

- Today Is Monday (Days-of-the-Week Song) - Mississippi Schoolchildren (vocals) Time: 1:04

- Mister Rabbit - Susie Miller and Two Boys (vocals) Time: 0:27

- Old John The Rabbit - Four Girls (vocals) Time: 0:13

- Rabbit Four Girls (vocals) Time: 0:38

- Rabbit in the Pea Patch - Angie Clark (vocal) Time: 0:41

- Old Grandpaw Yet - Mrs. Nell Hampton (vocal) Time: 0:45

- Roxie Anne - Samuel Clay Dixon (vocal) Time: 0:29

- Go To Sleep, Little Baby - Lester Powell (vocal) Time: 0:27

- Dors, Dors, 'Tit Bebe - Barry Ancelet (vocal) Time: 0:25

- Come Up, Horsey (Publ. TRO-Ludlow Music, Inc.) - Vera Hall (vocal) Time: 0:49

-

Old Mother Hippletoe: Rural and Urban Children's Songs

New World NW 291

The concept of childhood as a period requiring special institutions, such as schools, is fairly recent. For centuries children were integrated into the world of adults, regarded as a blessing because of their capacity to enter early into the family enterprise. Clothing, food portions, and work tasks were scaled to the size and strength of the children, and they were expected to undertake adult tasks. Almeda Riddle (New World Records NW 245, Oh My Little Darling, and 80294-2, The Gospel Ship), a singer from rural Arkansas, was brought up in such a tradition. As a young girl she followed her father and mother around just because she liked to be with them. But as soon as she was able, she aided her father at plowing the fields and sawing logs, and her mother at housekeeping, sewing, cooking, and child care.

Today we are losing sight of the family as a unit that produces and consumes. We take it for granted that both children and the elderly are removed from basic productivity. Children are sent to school, where, ideally, they will come to know more than their parents and in time "realize their potential." The elderly, bereft of their age-old responsibility to pass on traditions and wisdom as they care for the young, increasingly live in enclaves, passing most of their time in each other's company.

When children's life and labor were integrated with those of their elders, they mimicked them in their play, enacting scenes of child rearing, seasonal work, recreation, religious events, ill health and healing, aging, death, and burial. Bessie Jones (80252-2, Roots of the Blues, and 80278-2, Georgia Sea Island Songs), a black woman from a farming community in Georgia, has recounted playing at farmers-and- wives in her youth. Girls and boys played together with families of grass dolls made by the girls. They built miniature farms, gathered "crops" of seeds, and hitched up beetles to sardine cans to serve as horses drawing the crop to market. In "town" the "men" spent the money from the sale of the crop, while the "women" cared for the babies and scolded the children. On one occasion these playmates dug a fair-size grave for a play burial. Their mourning was interrupted just as they threw the first ceremonial shovel of earth over the child "corpse," and they all got thrashings.

In like fashion, the folk singers Sarah Gunning and her brother James Garland, from a Kentucky mining community, recall playing miners-and-wives. The boys dug large "mine shafts" into the hillside and sometimes had accidental cave-ins. The girls brought lunch to the "miners" and tended the home and the children.

The potter Lanier Meaders, son of a Georgia potter, has evidence of such playing at being grown-ups in a photograph of himself and his siblings with a tableload of miniature pottery made on their father's wheel and fired in a miniature kiln that they had built themselves. Their uncle took a load of their ware to sell along with the crocks, jugs, and churns turned by their father for use in food storage, preparation, and preservation. In the context of such play, the songs sung at work, church, and secular celebrations were rehearsed by the young. The elderly sometimes assisted these enactments with food and props, knowing that they were serious rehearsals for the labor and sex roles of adulthood. Children were the young ethnographers of their society, observing and judging critically the implications for culture stability and culture change in a changing world. In such traditional communities, where occupational strategies and cultural traditions were passed down by example and word of mouth, adults often unselfconsciously played the singing games we ascribe only to children today. Bessie Jones tells of the children, family, and neighbors gathering around evening fires to play together. Her formidable grandfather, who had been a slave brought from Africa as a child, felt strongly about the vocal and rhythmic aesthetic and the meaning of the games. Through them he interpreted life's perplexities and expressed his ethical system. The games were of souls who vowed through their words and motions to rise through hard labor and help others to rise with them, to avoid senseless conflict over possessions, to eat and share their food in hearty fellowship, to live morally and mete out punishment to transgressors, and to be proud and dauntless in the face of the terrible oppressions of white society. Another game tradition shared by grown-ups and children was that of the play-party. Folk singer Jean Ritchie, of Kentucky, tells of family play-parties at which her parents recalled their courting. The development and disappearance of the play-party dancing games afford a dramatic glimpse at the effect of changing cultural patterns on the traditional repertoire. Play-parties developed when waves of Calvinistic religious revival brought about the suppression of dancing to instrumental accompaniment in the mid-nineteenth century. Courting-age youngsters of religious communities called singing dances "just innocent games." The games were composed from elements of children's singing games judiciously combined with elements from traditional country dancing. By euphemistically calling these dances "games," "josies," "frolics," or "play-parties," thereby removing them from the onus of association with instrumental accompaniment and alcohol, adolescents and adults agreed to retain an important rural entertainment for the single purpose of socializing and courting, but an entertainment that could accompany communal occasions like barn raising, quilting bees, and corn shuckings. The play-party was dropped as courting patterns changed. Cars transformed country districts into suburbs of the nearest town, with its attractions of private courting— dance halls, movies, soda fountains, pool halls—and the car itself afforded privacy. At consolidated schools, which replaced oneroom schoolhouses, children were increasing] y segregated by age and sex, and long bus rides ate up free play time. High-school proms and going steady put the emphasis on couple dancing. At some country schools, teachers, under pressure from ministers and parents, attempted to stamp out playparties. At others, the tradition was appropriated for spring and fall celebrations. The profound break with tradition caused by the shift to urban occupations and urban schooling cannot be underestimated. Combined with the invasion of pop culture from movies, Tin Pan Alley, Nashville, radio, and television, these factors have effected a thorough cultural discontinuity. A few play-parties continue to be taught by enterprising schoolteachers. In the classroom, played by younger children, play-parties have lost their original courtship function. Only the children's singing games, which had been appropriated by the rebellious teenagers to de-emphasize the danciness of the event, reverted to the playground, where "London Bridge," "A-tisket, A-tasket," and "Little Sally Water" can still be found.

Given the integration of work and play in traditional communities, it should not be surprising that very few songs can accurately be categorized as children's songs. Children listened to whatever grown-ups sang. Carrie Grover (Side One, Band 1, Item 3), originally of Nova Scotia, describes her brothers and sisters sitting around the fire after dinner, when their parents had gone out visiting, "playing being grown-ups" by repeating the nightly ritual of singing lengthy old ballads and songs of their family repertoire, probably consoling themselves and fending off the fear they felt at being left alone. Several of the songs on Side One are grownup songs of great antiquity that have probably been perennial favorites with children, dealing as they do with subjects that in less disguised form would be considered unsuitable for children. For example, "Frog Went A-courtin' " is a story of a lively wedding interrupted by the untimely death of the groom, "Old Mother Hippletoe" is a song of the fox's unabashed murder of the gray goose, and "Robin Hood and the Peddler" is a song of unwarranted attack and attempted robbery. By requesting these songs, children could buffer their exposure to violence and death by the humor and warmth of the family. Along with the three ancient ballads mentioned above, two songs of relatively recent origin are not children's songs. "Round to Maryanne's," a drinking song in music-hall style, depicts the attractions of spending Sunday night at Maryanne's alehouse. "Little Sally Water," with its refrain borrowed from a venerable ring game, relates a story of love for love's sake and of blissful marriage. Two songs are responses to slavery. "Jim Crack Corn" reflects the delight of a house slave at his master's death. "The Gray Goose" portrays the death and resurrection of a tough and determined goose, implying the slaves' ability to rebound from all bodily attacks, including death itself. "Little Rooster" and "Oh, Blue" stand apart from the rest of these songs. The first expresses the delight of feeding one's animals and listening to their sounds; the second expresses desolation. Many adults can remember tearfully reading and rereading episodes like the death of Beth in Little Women or of the monkey in Toby Tyler. The wistful singing of "Oh, Blue" on this record suggests this catharsis. Side Two illustrates a variety of children's musical activities, including learning, playing, and sleeping. Games and sports are the most codified aspects of children's culture. Through them children learn the give and take of social transaction, learn to love each other and to share their innermost thoughts and feelings, to exercise leadership, foment and resolve conflicts, and form their own ethical systems. The girls' repertoire of jump-rope and ring games is composed of humorous elements that appeal to children. These games, favorites of six- to nine-year-olds, provide formulaic sanction for provocative dancing and wordplay, for revelation of love secrets, for teasing comments about grown-ups, and for plain competition. They are usually played to include all comers, jump-rope being preceded by a call for places in line, a ring game initiated by a pair of clapping girls and opening out into a circle to accommodate more and more children. The games represent an intersection of Afro- and Anglo- American cultural strains.

Games of all sorts are played in diverse languages: Spanish, Cajun French, native American tongues. Wherever such a language group preserves its cultural identity, children of the group are apt to learn its games and nursery lore. Sensitive teachers can encourage pride in such treasures, which are too often lost, dropped by children trying to adapt to Anglodominated culture. Games and sports are not shared by all children alike. Isolated for reasons of prejudice, home culture, ill health, time constraints, or personal inclination, children sometimes spend hours pouring their souls into song and musical mastery. We seldom find such ephemera on records: the virtuoso whistling, blowing of leaves, playing of the Jew's harp, cane fife, saw, bow, home-made banjo or guitar, and store-bought harmonica. Occasionally an impassioned childmusician grows up to entertain a broader community. Joe Patterson's panpipe playing (Side Two, Band 1, Item 3), carried uncharacteristically beyond childhood, vibrates with the joviality with which children entertain themselves in their solitary pursuits. Lonnie Pitchford (Side Two, Band 1, Item 2) plays a one-string "guitar" made of baling wire strung onto a tin barn. His song about a fight between his sister and brother, composed when he was ten, is the epitome of a child's rumination. Ed Young's early distinctive mastery of the cane fife (Side Two, Band 1, Item 1) enabled him to play for dances and stay out late without getting a beating. He continued to play for his community for most of his life. In addition to selections from the children's repertoire, Side Two contains three intersections of children's and adults' traditions: schooling chants. cheerleading, and nursery lore. In traditional communities, school was often taught by a more literate member of the community using methods and materials from oral tradition: songs, marching drills, rhyming chants, and moral plays from sacred tradition that warn young children about worldly ways. These teachers also used written materials that reflected oral tradition. Such were the books of singing sums and ABCs. "B-A-Bay," "Dos y Dos Son Cuatro," and "Today Is Today" derive from the schooling-chant tradition. Cheerleading has developed in the century as an accompaniment to college sports events. Adults teach the art to girls as a highly competitive activity. On the playground, however, cheers serve other purposes and aesthetic criteria, as is shown in the black girls' elaboration of the medium, elements of which derive from their African heritage.

In nursery lore, finger naming and facial play, knee bouncing and tickling, songs and games, sayings for feeding and dressing, and lullabies are used by young and old alike to entertain a new member of the family. The record ends with three timeless lullabies. In summary, Side One contains songs from the traditional adults' repertoire that children enjoy and that adults think are all right for them to enjoy. Like many of the Grimms' Household Tales, most of the songs were originally conceived by adults for adults. Their co-option for children has taken place relatively recently, probably during the period when childhood was being defined as a separate status and a suitable repertoire for children's songbooks and schooling was developed.

Side Two contains games, tunes, and songs from the children's repertoire, past and present, and songs from the intersection of adults' and children's repertoires. Here we can observe the reworking of adult materials into forms suitable to children's concerns, forms that convey the intensity, vitality, and originality of America's playground poets.

Band 2, Items 3-5

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abrahams, Roger D. Jump Rope Rhymes: A Dictionary. ("American Folklore Society

Bibliographical and Special Series,"

Vol, XX.) Austin: University of Texas Press, 1969.

Baring-Gould, William S., and Baring-Gould, Ceil. The Annotated Mother Goose.

New York: Clarkson Potter, 1962.

Botkin, Benjamin A. The American Play-Party Song. New York: Ungar, 1963. Reprint

of 1937 edition.

Gomme, Alice Mertha. The Traditional Games of England, Scotland and Ireland.

Vols I and II. New York: Dover, 1964.

Reprint of 1894, 1898 edition.

Huizinga, Johan. Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play Element in Culture. Boston:

Beacon Hill, 1955. Reprint of 1951

edition.

Jones, Bessie, and Hawes, Bess Lomax. Step It Down: Games, Plays, Songs, and

Stories from the Afro-American Heritage.

New York: Harper & Row, 1972.

Knapp, Mary, and Knapp, Herbert. One Potato, Two Potato: The Secret Education of

American Children. New York:

Norton, 1976.

Lomax, Alan. Folksongs of North America. New York: Doubleday Doran, 1960.

Nathan, Hans. Dan Emmett and the Rise of Early Negro Minstrelsy. Norman:

University of Oklahoma Press, 1962.

Newell, William Wells. Games and Songs of American Children. New York: Dover,

1963. Reprint of 1903 edition.

Opie, Iona, and Opie, Peter. Children's Games in Street and Playground. Oxford:

Clarendon, 1969.

____. Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes. London: Oxford University Press,

1961.

Seeger, Ruth Crawford. Animal Folk Songs for Children. New York: Doubleday

Doran, 1950.

Sutton-Smith, Brian. The Folkgames of Children. Austin and London: American

Folklore Society, University of Texas

Press, 1972,1974.

SELECTED DISCOGRAPHY

Afro-American Blues and Game Songs. Alan Lomax, ed. Library of Congress AAFS-14.

American Folk Songs for Children. ("Southern Folk Heritage Series.") Atlantic

1350.

Been in the Storm So Long. Folkways FS-3842. Spirituals, shouts, and

children's-games songs from Johns Island, S.C.

Millions of Musicians. Tony Schwartz, ed. Folkways S5-5560.

One Two Three and a Zing Zing Zing. Tony Schwartz, ed. Folkways FC-7003. Street

games and songs of New York City

children.

Play and Dance Songs and Tunes. Benjamin A. Botkin, ed. Library of Congress

AAFS-L9.

Skip Rope. Folkways FC-7029. Thirty-three skip-rope games recorded in Evanston,

Ill.

Step It Down. Mary Jo Saran, ed. Rounder 8004.

Videotapes with Teacher's Manuals (all Office of Museum Programs, Smithsonian

Institution, Washington, D.C.)

Stu Jamieson Teaches Play-Parties from the Southern Anglo-American Tradition.

Kate Rinzler, ed.

Bessie Jones Teaches Children's Games from the Southern Black Tradition. Kate

Rinzler, ed.

Alison McMorland Teaches Children's Games from the British Tradition. Kate

Rinzler, ed.

Side One

Total time 27:02

Band One

FROG WENT A-COURTIN' . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2:46

Almeda Riddle, vocal

OLD MOTHER HIPPLETOE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2:12

J D. Dillingham, vocal

ROBIN HOOD AND THE PEDDLER (Child 132) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2:44

Carrie Grover, vocal

BOBBY HALSEY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2:15

Probably E. C. Ball, vocal and fiddle

Band Two

ROUND TO MARYANNE'S . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .3:04

Kenneth Atwood, vocal

DIEZ PERRITOS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1:52

Arseńo Rodriguez, vocal and guitar

LITTLE SALLY WATER . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .2:14

Captain Pearl R. Nye, vocal

JE ME SUIS MIS-T-Ŕ COURIR . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1:32

Sabry Guidry, vocal

JIM CRACK CORN . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1:23

Uncle Alec Dunforn, vocal

Band Three

LITTLE ROOSTER . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1:50

Almeda Riddle, vocal

OH, BLUE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1:41

Thelma, Beatrice, and Irene Scruggs vocals

THE GRAY GOOSE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .3:14

Washington (Lightnin'), vocal

Side Two

Total time 22:45

Band One

UNTITLED FIFE TUNE WITH CLAPPING ACCOMPANIMENT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . .1:32

Ed Young, cane fife: Bessie Jones and Georgia Sea Islanders, clapping

APPLE TREE SONG . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2:20

Lonnie Pitchford, vocal and one-string "guitar"

CATFISH . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1:19

Joe Patterson, vocal and panpipe

Band Two

SALLY DIED; RONALD McDONALD; GEORGE WASHINGTON;

BUMP, BUMP, BUMP; SALOME; ZOODIAC; ZING-ZING-ZING . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . .4:07

Schoolchildren from Washington, D.C.. vocals

Band Three

THINK; YOUR LEFT; CHEERING IS MY GAME;

HOLLYWOOD NOW SWINGIN'/ DYNOMITE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . 2:28

Barbara Borum and other schoolgirls from Washington, D.C., vocals

Band Four

ALL HlD . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1:44

Bessie Jones, vocal

I'M RUNNIN' ON THE RIVER . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 0:30

Three 12-13 year-old girls, vocals

LA PUERTA ESTA QUEBRADA . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .0:30

Govita Gonzales and group, vocals

OJIBWA WAR DANCE SONG . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .0:37

Albert, Vernon, and James Kingbird, vocals; drum accompaniment

CHARIOT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .0:47

Group of girls, vocals

Band Five

DOS Y DOS SON CUATRO (Mexican counting song) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .0:25

Alicia Gonzalez, vocal

B-A-BAY (spelling song) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .0:19

Mrs. A. P. Wilson, vocal

TODAY IS MONDAY (days-of-the-week song) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1:20

Mississippi schoolchildren, vocals

Band Six

MISTER RABBIT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1:25

Susie Miller and two boys, vocals

OLD JOHN THE RABBIT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 0:47

Four girls, vocals

RABBIT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 0:56

Four girls, vocals

Band Seven

RABBIT IN THE PEA PATCH . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 0:47

Angie Clark, vocal

OLD GRANDPAW YET . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 0:47

Mrs. Nell Hampton, vocal

ROXIE ANNE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .0:35

Samuel Clay Dixon, vocal

Band Eight

GO TO SLEEP, LITTLE BABY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .0:35

Lester Powell, vocal

DORS, DORS, 'TIT BEBE . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .0:32

Barry Ancelet, vocal

COME UP, HORSEY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1:03

(publ. TRO-Ludlow Music, Inc.)

Vera Hall, vocal

Full discographic information for each selection may be found within the

individual

discussions of the works in the liner notes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to the following for furnishing tapes for use in assembling the master

tape: The Library of

Congress, The Smithsonian Institution, Ralph Rinzler, Kate Rinzler, Barry

Ancelet, Bess Hawes,

Tom Vennum, and Alan Lomax.

"Frog Went a-Courtin' " appears courtesy of Collegium Sound, Inc., and "Little

Rooster," courtesy of Atlantic Records.

Thanks to the following performers for their special help: Almeda Riddle;

Beatrice, Thelma, and Irene Scruggs; Bessie

Jones; Hannah Young; Lonnie Pitchford; Alicia Gonzalez; and Mrs. A. P. Wilson.

Special thanks to Joseph Hickerson and

Sam Brylawski of the Library of Congress for their continuous cooperation and

help.

Program Consultants: Kate Rinzler, Bess Lomax Hawes

Rerecording engineer: Art Shifrin

Mastering: Ted Jensen, Sterling Sound

!1978 © 1978 Recorded Anthology of American Music, Inc.

FOR NEW WORLD RECORDS:

Herman E. Krawitz, President; Paul Marotta, Managing Director; Paul M. Tai,

Director of Artists and Repertory; Lisa

Kahlden, Director of Information Technology; Virginia Hayward, Administrative

Associate; Mojisola Oké, Bookkeeper.

RECORDED ANTHOLOGY OF AMERICAN MUSIC, INC., BOARD OF TRUSTEES:

Richard Aspinwall; Milton Babbitt; Emanuel Gerard; Adolph Green; David Hamilton;

Rita Hauser; Herman E. Krawitz;

Paul Marotta; Robert Marx; Arthur Moorhead; Elizabeth Ostrow; Cynthia Parker;

Don Roberts; Marilyn Shapiro;

Patrick Smith; Frank Stanton.

Francis Goelet (1926–1998), Chairman

2002 © 2002 Recorded Anthology of American Music, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in U.S.A.

THIS DISC WAS MADE POSSIBLE BY GRANTS FROM THE ROCKEFELLER FOUNDATION AND THE

NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE ARTS

NO PART OF THIS RECORDING MAY BE COPIED OR REPRODUCED WITHOUT WRITTEN

PERMISSION OF R.A.A.M., INC.

NEW WORLD RECORDS

16 Penn Plaza #835

NEW YORK, NY 10001-1820

TEL 212.290-1680 FAX 212.290-1685

Website: www.newworldrecords.org

email: info@newworldrecords.org

LINER NOTES Recorded Anthology of American Music, Inc.