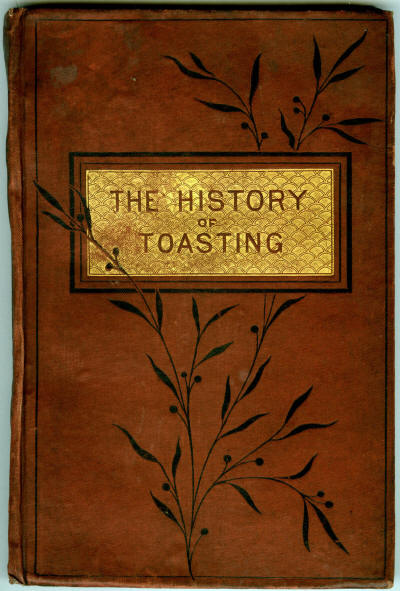

THE

HISTORY OF TOASTING,

OR

DRINKING OF HEALTHS

IN ENGLAND.

BY THE REV.

RICHARD VALPY FRENCH,

D.C.L., F.S.A.,

Hector of Llanmartin and Wilcrick.

LONDON:

NATIONAL TEMPERANCE PUBLICATION DEPOT,

337, STBAND, W.C.

PKEFACE.

This little work is the substance of a paper

read at a

Conference held at the Shire Hall, Gloucester, October 11th,

1880. The chair was taken by Dr. Kayner Batten, and same

important comments were made upon the Paper by the Rev.

Prebendary Grier, and Samuel Bowly, Esq., President of the

National Temperance League. It is published in compliance

with a wish expressed upon the platform by Mr. Varley that

it might assume some permanent form.

Llanwiartin Rectory,

April 4th, 1881.

DEDICATED

TO MY FRIEND

Dr. B. W. RICHARDSON, F.R.S.,

OF WHOM I AM AN ARDENT ADMIRER,

AND TO WHOSE SCIENTIFIC RESEARCHES

I AM DEEPLY INDEBTED.

mam

M

CONTENTS.

Chapter I. Pre-historic ... ... ...

9

Chapter II. Toasting among the Greeks and

Romans ... ... ...

18

Chapter III. Toasting among the Saxons, Danes,

and Norfch-men ... ...

28

Chapter IV. Toasting from the Twelfth to the

Sixteenth Century ... ...

53

Chapter V. Toasting in the Seventeenth Century

64

Chapter VI. Toasting in the Eighteenth Century

80

Chapter VII. Toasting in the Nineteenth Century

86

Chapter VIII. Conclusion ... ... c..

97

CHAPTER I.

Pke-historic.

The present is an age. of severe criticism. Men,

customs, institutions, ceremonies, are submitted to

test; if they stand the crucible, well and good ; if not,

they are rejected. It is proposed in the present paper

to drag to trial a ceremony which can plead antiquity,

prevalence, and catholicity, viz., that of

health-drinking

or. toasting.

An extract from the report of an educational

dinner

may serve as a plea for investigating the history and

questioning the good sense of the national accompani-

ment of public feasts. " The cloth having been

withdrawn, after the usual loyal and national toasts,

6 The Royal Family ' was drunk; ' Her Majesty's

Ministers ' were drunk ; ' The Houses of Parliamentr

were drunk; < The Universities of Scotland' were

drunk;

' Popular Education in its extended senser

was drunk ; 'The Clergy of Scotland of all Denomi-

nations ' were drunk ; 'The Parish Schoolmasters'

were drunk; othei^ parties not named were drunk;

' The Fine Arts' were drunk; ' The Press' was

A

10

THE HISTORY OF TOASTING.

drunk; 'The Strangers' were drunk."

Such is the

description of the after-dinner arrangements. And

they are instructive, as you would expect every part of

an

educational dinner to be. Let us try, %then, to

derive the instruction they contain. And who can lay

better claim to impart it than an educationalist, one who

but the other day, occupied that honourable position,

a patient instructor of the youthful mind ? Duty

demands that they should have a spokesman to vindi-

cate their postprandial claims to historical antiquity.

It must have often happened, on the occasion of

some public banquet, when the host or president of

the entertainment, or, as at the dinners of the Lord

Mayor and the various city companies, an official

known as the toastmaster has gravely called upon the

guests to drink a glass of wine or bumper in honour

of some person or institution, that persons of an

inquiring turn of mind have asked themselves " What

is the origin, what is the meaning of this custom ?'r

It is more than doubtful if anyone can assign its

precise origin. Better is it frankly to avow at the

outset that materials are not forthcoming which might

unveil the secret who it was that proposed the first

health, what was the occasion thereof, and what were

the circumstances leading thereto. Evidence is forth-

coming that the practice obtained in ages of remote

antiquity—ages of which the history at one's disposal

is sparse and often mythical.

■ \

THE HISTORY OF TOASTING.

11

Were the subject to be treated exhaustively, it

would be necessary to enquire into the origin of

drink

itself, and one's thoughts would naturally turn to the

first historical vine-culture, the first wine-drinking,

the first drunkenness, the first curse, when, in the

words of the sacred narrative, " Noah began to be an

husbandman, and planted a vineyard, and drank of

the wine and was drunkon, and awoke from his wine

iind said

' Cursed be Canaan.'" But although the

patriarch Noah is the first

on record who planted a

vineyard, it is scarcely to be supposed tlifit the culture

of the vine was not practiced before his time. Milton

seems to have thought that that fruit contained at any

rate the potentiality of intoxication, when he wrote:—

* Soon as the force of that fallacious fruit,

1 That with exhilarating vapour bland

1

About their spirits had

play'd, and inmost powers

1 Made err, was now exhaled ;** And again :—

4 As with new wine intoxicated both

' They swim in mirth, and fancy that they feel

* Divinity within them.'

It is curious that the Chaldee paraphrases

support

the same idea; thus the Targum of Jonathan Ben

Uzziel gives the legend that Noah 'lighted upon a

vine which the flood had carried away out of the

* Milton's Paradise Lost, Lib. ix

12

THE HISTORY OF TOASTING.

Garden of Eden, that he planted it in a

vineyard, and

in that very day it blossomed, and its grapes ripened/

which he pressed out ; and he drank from the winer

and was drunk.'

The Rabbins were of the same belief.

Dr. Light*

foot maintains it in his Talmudical Exercitations on

fit. Luke. Oral tradition is in harmony. The natives-

in the Island of Madagascar believe that the four

rivers of paradise consisted of milk, honey, oil, and

wine; and that Adam having drunk of the wine, and

tasted of the fruits contrary to the command of God7

was driven from the garden.*

Dr. Kennicott, the celebrated Hebrew

Scholar of

the last century, translates Genesis ix. 20, 'Noah

continued

to be a husbandman/ as though this occu-

pation had simply been interrupted by the flood*

Indeed, what can be implied in our Lord's words,

'as the days of Nee

were, so shall also the coming

of the Son of Man be. For as in the days that were

before the flood they were eating and drinking, marry*

ing and giving in marriage, until the day that Noe

entered into the ark, and knew not until the flood

came, and took them all away; so shall also the coming

of the Son of Man be/f but that indulgence in intoxi-

cating drink formed an item in that catalogue of guilt

for which the world was doomed to deluge ? If this

* Cited by More wood, 'Hist, of Ineb. Liq.' p.

3.

t Matt. xxir. 37-39.

THE HISTORY OF TOASTING.

1$

be so, how remarkable the coincidence that the

same

-sin was the first recorded instance of fall after that

infliction !

Lastly, a living Divine discussing the question

whether the properties of wine to produce the given

effect upon Noah were till then unknown, remarks :

4 An attentive perusal of the narrative is sufficient to

render that hypothesis at least very doubtful.'*

Procopius believed that the vine was known

before

Noah's time, but not the use of wine,

Father Frassen, writing from an entirely

different

point of view, contends that there is no likelihood that

men contented themselves with drinking water for

1500 years together. He argues that these first men

of the world were endued with no less share of wit

than their posterity, and consequently wanted no

industry to invent everything that might contribute to

make them pass their lives agreeably. Noah there-

fore, according to this writer, was not the inventor of

the grape ; he merely planted new vines. With this

view compare that of Becman (Annal. Hist.)

So much for authority. What does common sense

iseem to suggest? In the first place the process of

obtaining wine from the grape is simple and obvious,

In the next place the sweetness and succulency of the

juice must have suggested the desire to separate the

* Dean Close ' The Book of Genesis,' Serin, ix.

14

THE HISTORY OF TOASTING.

juice from the fruit and use it as a

drink. The juice

when separated spontaneously ferments.* The re*

markable appearance of the fermentation would

stimulate curiosity to insure the development of the

process. Added to this, the smell and taste would

have become vinous. It would be essayed, and the

effects of it would be so enlivening that the process*

producing such influences would be repeated. It

would seem, therefore, highly probable that from the

very earliest times vines were planted and wine manu-

factured.

It would be deeply interesting to trace

the history

of drinks and drinking, in their march into Western

Europe from their cradle the East. There is generally

a basis of truth underlying the absurdities of myth-

ology. Osiris may not have been son of Ham, the

son of Noah; but the myth points to the struggle of

history to connect the vineyards of Egypt with the

vineyard-planting of the Patriarch. The same remark

will apply if, as others have it, Mizraim the grandson

of Noah were but the counsellor and friend of Osiris.

Upon this Osiris (identified with Bacchus) Diodorus

Siculus would father Egyptian vine-culture. 'He taught

the Egyptians the management and use of the vine,

* Although not immediately, except -when

subjected to excessive

temperature. See some admirable remarks on this subject in a

pamphlet by Dr. Norman Kerr, entitled '* Unfermented Wine A

Fact."

THE HISTORY OF TOASTING*.

15

as also of wine apples, and other

fruit.'* Again, in

his first book, he says that Osiris taught the people to

make a drink from barley, not much exceeded by wine

in smell and taste.

Customs immigrated together with

peoples. The

Greeks and Eomans learnt from the Easterns the

culture of the vine. The Britons learnt it from the

Komans. And there is a strong presumption that

toasting or the drinking of healths is of much older

date than the Saxon origin usually ascribed to the

custom. Its origin

as far as we are concerned, is

Roman.

The absolute origin of toasting

is unknown. It is

however most natural to suppose that when the off-

spring of Noah dispersed and carried with them the

art of cultivating the vine and of wine-making, it

often happened that some parched and weary wayfareif

would receive a draught of wiue with gratitude, and

would express his thankfulness to the bestower in the

most complimentary terms at his disposal. In the

dry burning countries of the East, drink would often

be more acceptable than food, and much more scarce.

"Water in such regions is not only not abundant, but

often not to be obtained. Wine would in such cases

be of the utmost value. Moreover, the agony of thirst

is instantly relieved by the act of drinking, whereas

* Died. Sic. Lib. in.

16

THE HISTORY OF TOASTING.

the pangs of hunger are not dissipated with the

first

mouthful of food. Drinking would thus come to be

considered the most important preservative of exist-

ence, and every occasion thereof would be calculated

to excite in the drinker an expression of grateful

thanks. Whoever provided the draught would invari-

ably be looked upon as a benefactor. Instinctively,"

almost, the drinker would look about for some fellow-

being to whom he might express in words the kindly

emotions that filled his breast ; and thus, it appears

not unreasonable to surmise, arose the custom of

paying compliments in connection with the act of

drinking. How this practice developed into the cus-

tom of honouring absent friends, esteemed heroes, and

finally gods,* or anything thought worthy of veneration,-

it is not difficult to imagine. Hence we can understand

how, after a time, drink-offerings came to be considered

as peculiarly appropriate in the religious rites and

observances of primeval races.

This theory is ventured, because other writers

who

have traced the habit of health-drinking to sacrificial

usage and Pagan origin, have been content to know

that at a very early period of the world's history,

* Doran remarks that when the Greeks gave great

entertainments,

and got tipsy thereat, it was for pious reasons. They drank deeply

in honour of some god. They not only drank deeply, but progress-

ively so ; their last cup at parting was the largest, and it went by

the terrible name of the cup of necessity. There was a headache of

twenty-anguish power at the bottom of it.—Tabic Traits,

p. 515.

THE HISTORY OP TOASTING.

17

drink was an important factor in

various religious rites.

Though we do not find in the Bible any direct

allusions to one person

drinking to the health of or in

honour of another, there are passages which lead us

to conclude that the practice was not entirely unknown.

It is hardly probable that Ben-hadad and the thirty-

two kings, his companions, would drink themselves

drunk in the pavilions without some interchange of

courtesies (1 Kings xx. 16). And when Belshazzar

and his fellow-revellers feasted, the Bible narrative

almost inclines us to believe that the king on that

occasion filled precisely the same office as that known

amongst the Greeks as

symposiarch, and amongst the

Romans as arbiter bibendi—he

first tasted the wine,

then ordered what vessels they were to drink from,

and then " they drank wine and praised the gods."

(Dan. v. 2-4.) Again, the mention of those that

" drank wine in bowls " (Amos vi. 6.) has probably

some reference to a special form of ceremonious

drinking. It would be interesting, too, did space

permit, to inquire into the whole subject of drink-

offerings (Gen. xxxv. 14) which were made, not only

to the Almighty, but also to false gods (Jer. vii. 18)

and to ascertain, if possible, how they were connected*

with the custom of honouring or complimenting living

princes, heroes, and friends.

CHAPTER II.

Toasting among the Geeeks and Romans.

With the foregoing remarks as to the

possible origin

of health-drinking, we pass on to a time of which we

possess somewhat more reliable and detailed informa-

tion. Whether the old and original ancient Briton of

Celtic origin, who, before Cassar landed in this country,

passed a somewhat miserable sort of life, some of them

burying themselves up to the neck in the earth when

it was cold weather, living on herbs, roots, and nuts ;

whether they ever quaffed a born of beer, which, we

are told, they knew how to brew from barley, to the

health of their wives, or toasted the woad-staiued

maid of their affections in a bumper of the same

liquor, we are not prepared to state. But at any rate

we know that in the year 55 B.C., when Cassar invaded

Britain, the inhabitants, who transmitted to writing

no accounts whatever of the doings of their heroes or

kings, keeping but the sparsest record of public or

private accounts, grew some corn, the chief of which

was barley, of which they made their drink, Cuno-

belin, King of Britain in the time of Augustus (b.c. 23)

THE HISTORY OP TOASTING.

1£

coined money stamped with his portrait,

and in other

respects followed the manners and customs of the

Komans, amongst which it is reasonable to suppose

he would imitate their banquetings and entertainments.

It will therefore be interesting to glance at the drink-

ing ceremonies and usages of that nation, borrowed,

as they were, in the main from the Greeks, to whom

the custom had been handed down from remote ages,

as can be proved from Homer.

But before enquiring into the drinking

habits of the

Romans, those of the Greeks demand some notice.

For the benefit of those who desire full information on

this subject it may be mentioned that a work of the

Egyptian Grammarian Athenseus, entitled " The Deip-

nosophists, or, The Table Talk of the Sophists," is

full of information.

Homer is our principle reliable

authority for the

early manners of the Greeks. He represents the

banquets of his time as simple and unpretending.

Many species of wine were in vogue; some of great

strength, notably the Maronean wine, which would

bear being reduced by water to one-twentieth its

strength.

The guests drank one another's

health, thus Ulysses

pledged Achilles in the words

<sx<«/>\ 'AxiXtv."*

In later times the first meal in the

day derived its

* Homer. II. I' 225.

-20

THE HISTORY OF TOASTING.

name from the drink which formed a part

of it. The

unmixed wine {dKparos) gave the name to the breakfast,

rvncparicrfJia.

It appears that the Greeks did not

drink wine at

dinner till the first course was finished, often not till

the meal was concluded. Herein they differed from

the Romans. When the wine was brought on, the

first ceremony was—pouring out a libation to the

■" good spirit" After that

mixed had been substituted

for unmixed wine, the guests at once drank the health

of " Jupiter Preserver."

The drinking proper began after the

meal. It was

ihen that (as Plato expresses it) they " turned to the

drinking."

Drinking bouts were great

features with the Greeks,

answering pretty much to the comissatio or

convivium

of the Romans. The drinking at these symposia was

under the regulation of a master of the revels, termed

a

" Symposiarch." He directed the order and quantity

of the drinking. The

drinking of healths formed an

important feature. They drank to the health of one

another, each one being specially careful to

pledge the

person to whom he passed the cup.*

It should have been observed that after

the first

dinner course, the guests having washed their hands

* For more particulars under this head, see

Plat. Symp. IV. Diod.

Sic. IV. Xen. Sijnip. II. Lucian Gall. XII. Athen. XI. Smith,

J)ic, Antiq. Becker's CharicUs^ and Becker's Gallus.

THE HIST0KY OF TOASTING.

21!

passed round a large goblet of

undiluted wine, of which

each person poured out on the ground a few dropsr

and then drank a little, during which time the paean

was usually sung. This looks like the

grace-cup of

later days, and the loving-cup of our own time which

still passes round at some of the City Companies'

feasts. A loving-cup on a magnificent scale was that

which Alexander the Great is reported to have pro-

vided after arranging the difficulties betwreen the

Persians and the Macedonians, when nine thousand

men drank from the same bowl to the honour of

Jupiter, and in token of friendship.

That the custom of health-drinking had

been

handed down to the Greeks from very remote ages is

clear from passages in Homer unmistakably referring

to it.*

Among the Komans luxury was carried to

an un-

bounded extent, and drinking was more indulged in

by them than by the Greeks. Not only was the wine

and water introduced at an early period of the dinner,

which meal was often prolonged for many hours in

order that drinking might be kept up, but

comissa-

tiones, or drinking bouts pure and simple, at which

the only object was the consumption of wine, and

which were often only concluded at a very late hour

of the night, were frequently organised. At these

* Horn. II. IV. 4, IX. 225.

22

THE HISTORY OF TOASTING.

drinking bouts no food was taken, save

as a relish to

the wine. Mention of healths drunk by the Eomans

occurs in many writers, and that this custom ,was

derived from the Greeks there is good reason to suppose

from Cicero's speaking of drinking

Grceco More (Verr.

i. 26), and again, " Grseci enim in conviviis solent

nominare cui poculum tradituri sunt " (Tusc. i. 40).

The following are specimens of Eoman

forms of

toasts :—

"Pro te fortissime vota,

Publica suscipimus : Bacchi tibi sumimus haustns."

And in Plautus we read: "

Bene

vos, bene vos, bene

te, bene me, bene nostram etiam Stephanium."

The Senate decreed that men should

drink to the

health of Augustus in their entertainments, audi Fabius

Maximus ordered that no man should eat or drink

before he had prayed for him and drank his health.

A later writer, Sigismundus, records that it was a

custom of the ancient Muscovites and Kussians to

drink

pro sanitate C<zsaris> and of others in high posts,

so that none dare refuse to drain the cup, no matter

how intoxicated they might become in so doing.

Apart from State and patriotic toasts,

the Eoman

gallants commonly pledged their mistresses in their

cups (Martial, Lib. i. Ep. 72). The survival of this

custom to the seventeenth century is clear from a pas-

sage in " Le nebuchement de 1'Ivrogne," by Guillaume

THE HISTORY OF TOASTING.

Colletot, printed in Paris, 1627, in which one

of the

characters drinking to the health of Clovis, his mis-

tress, exclaims—

44 Six-fois m'en vas boire au bon nom

de Clovis,

Clovis, le seul desir de ma chaste pensee."

In Rousaud's

" Bacchanales" the same

custom is

referred to, when a gallant drinks nine times to his

mistress Cassandra :—

44 Neuf fois, au nom de Cassandre

Je vois prendre,

Neuf fois du vin da flacon ;

Afin neuf fois le boire

Ejl memoire

Des neuf lettres de son nom."

The custom of drinking " three times three " was

apparently in the time of Horace a mark of honour to

the Graces and Muses:—

44 Tribus aut novem

44 Miscentur cyathis pocula commodis

Qui Musas amat impares,

Ternos ter cyathos attonitus petet

Vates."

—Lib. Ill, Carm. XIX.

24

THE HISTORY OF TOASTING.

. Another of his remarkable allusions is to be

found

in lib. i. Carm. xxvii. :—

" Voltis severi me quoque sumere

Partem Falerni ? Dicat Opuntise

Frater Megillae quo beatus

Volnere, qua pereat sagitta,

Cessat voluntas ? Non alia bibam

Mercede."

But this was no new mode of doing homage to the

fair sex. Two hundred years before, Theocritus of

Syracuse had told how a lover mingled his love in his

liquor;* and elsewhere he describes a banquet where,

as they grew warm with wine, each man filled his cup

and named whom he pleased, though compelled to

drink to someone.

Athenams describes minutely the drinking vessels

of the Komans. Amongst these were the

Asaminthus,

or vessel in form of a seat. Calices of many species.

The

Cyathus (of which we read that in drinking to a

mistress the Romans took as many

cyathi as there

were letters in her name). The Gaulus,

or round

drinking vessel. The Olmos, a drinking vase of ox-

horn shape. The

Ehytium or Rhyton, the original

form of which was also the horn of an ox, the lower

end of which was afterwards ornamented with grotesque

* Thcocr. Idyll II. 151.

THE HISTORY OF TOASTING.

25

heads. Dr. Smith mentions that

specimens of these

have been discovered at Pompeii.* The Triens, a

measure of four cyathi, called also

Triental\ The

number and variety of these vessels is an evidence of

the general consumption of wine at the period. They

were made of all sorts of materials, of pottery, glass

or copal resin, wood, crystal, horn, silver, bronze, and

other substances. They were of all sizes from the

Cyathus the unit measure to the huge elephant-vase.

" 'Tis a mighty cup,

Pregnant "with double springs of rosy

wine,

And able to contain three ample

measures,

, The work of Alcon. When I was at

Cypseli,

Adaeus pledged me in this

self-same cup."|

Thus much for toasting amongst the

Eomans, the

only civilised nation who visited England up to the

fifth century, except the Carthaginians and Phoeni-

cians, who simply came over for trade purposes, and

do not seem in any way to have influenced the manners

of the inhabitants. If these customs, or some of

them, had not been adopted by the British before

Agricola's time, it is quite certain that when that

most diplomatic of governors held sway here, he would

teach

thejeunesse doree and coming men of his time

* Museo Borbonico. Vol. VIII. 14. v. 20. f

Persius. Sat. III. 100

X AthenseuF, p. 747. Samuelson, Hist, of Drinlr, p. 9?,

B

26

THE HIST0BY OF TOASTING.

to drink healths to the Emperor, and to

toast the

reigning British belles in brimming bumpers. He

assisted them to build temples, forums, and houses

such as they had never before seen, and by his adroit

flattery he persuaded them to study letters. The

Roman dress, language, and literature spread amongst

the natives, and of course with Roman civilisation,

Roman luxury was introduced. Spacious baths, ele-

gant villas, and sensual banquets, with their attendant

revelry and intoxication, speedily became as palatable

to the new subjects as to their corrupt masters. And,

though we have no instances recorded, there can be

no reasonable doubt that the cups of mead and wine

and the horns of barley beer circulated freely, and

were drunk by the hilarious Britons in honour of and

pro sanitate of everybody and everything.

It seems, then, clear that

health-drinking in England

finds its origin in Roman rather than Saxon influence,

There are those who imagine that it is of Scandinavian

origin, an opinion which they have formed from the

writing of Snorro Sturleson, who says it was customary

to drink the health of Christ, St. Michael, and other

Saints, in the place of Odin, Niord and Frey, the early

objects of their national idolatry.* Mr. Morewood

refers this Scandinavian -practice to the Greeks, by

whom three cups were always taken at their meals ;

* Henderson's

Iceland, II. 67.

THK HISTOBY OF TOASTING.

27

the first dedicated to Mercury, the

second to the

Oraces, and the third to Jupiter, They also drank

healths to all their tutelary deities; to Mercury on

going to bed, in order to have pleasant dreams ; to

Jupiter, as their great preserver, and to other gods for

similar reasons.* The form of toast of the old North-

men is given by Christ, de Scala.t

" Let us drink

ihis cup in the name of the holy Archangel Michael,

begging and praying him to introduce our souls into

the peace of eternal exaltation."

* Morewood,

Hist. Ineb. Zig. t life

of & Wenceslaus.

CHAPTER III

TOASTING AMONG THE SAXONS, DANES AND NORTH-MEN.

Quaint old Geoffrey of Monmouth, whom

Strutt calk

"that arch-dreamer," records in his Chronicle a

memorable health. After Hengist and Horsa had

been invited by the British King Vortigern to assist

him in repelling the raids of the Picts and Scots,

these brothers set up a considerable establishment,

and invited Vortigern to inspect their new buildings

and new soldiers. A banquet followed, at the conclu-

sion of which

a a young lady came out of her chamber

bearing a golden cup full of wine, with which she

approached the King, and making a low courtesy,

said to him, <

Laverd King, Wacht heiV The king

was attracted with her beauty; and calling to his

interpreter, asked him what she said, and what answer

he should make her. * She called you Royal Lord,

said the interpreter, ' and offered to drink your health;

and your answer to her must be "

Drinc heil" ' Vor-

tigern accordingly said " Drinc>heil"

kissed the lady,

who was the most accomplished beauty of the age, and

then drank himself. After this, the monarch made

Tiolent love to the girl, and becoming intoxicated with

THE HISTORY OF TOASTING.

29

the variety of the drinks, bargained with

Hengist for

the lady, for whom he agreed to give the province of

Kent; they were married that very night, but we are

not told whether the king got sober, though Geoffrey

says that he became exceedingly delighted with his

wife, and that from that time it became the custom

in Britain that he who drank to anyone said, "

Wacht

heil" and he who pledged him answered, "Drincheil"

Some writers have concluded from this account that

Kowena introduced the custom of health-drinking into

England ; but there is nothing whatever to warrant

such a conclusion—though possibly the expression

Wacht keil (or was hell), and Drinc heil may have

become more popular through their use on that

occasion. The British King Vortigern asked his

interpreter the meaning of the Saxon words, for he

was probably only acquainted with the Keltic language;

gallantry would supply his reason for asking what

reply he should make, desiring as he did to win the

girl's favour by answering in her own tongue.

In illustration of the words

Drinc-heil

was-heil, may

be cited the last stanza of the earliest existing carol

known, a carol found on a blank leaf in MS. Bibl.

Keg. 16, E. V1IL, in the British Museum, probably in

use among those professional minstrels who wandered

from castle to castle of the Norman nobility.

" Lords, by Christmas and the host

Of this mansion, hear my toast—

so

THE HISTORY OF TOASTING.

" Drink it well-

Each must drain his cup of wine,

And I the first will toss off mine:

Thus I advise,

Here then I hid you all Wassail,

Cursed he he who will not say Drink hail."

This rendering is by the Author of

Christmas with

the poets.

Much has been written on the subject of

Wassailing*

The derivation of the term is disputed. More wood

considers it to be compounded of

Waes wishing, and

Mel health. Dr. Brewer derives it from

Wees heel

water (of) health ; as was given by JBoag in the

Imperial Lexicon. Richardson derives it from Wees-

hale

or hal wees, salvus sis, mayst thou be in healths

Dr. Ogilvie suggests Sax,

wcese, perf, subj, second sing.

of wesan to be, and

hcelu, whole, " would thou wert

whole."

Just as the origin of toasting was put

down to the

Saxon, so was that of wassailing. This is a mistake

likewise. The custom is much older. It is mentioned

in Plautus, a Roman writer of the third century B.C.,

and existed among the Britons.* The

Wassail bowl

was an important accessory to Christmas, the New

Year, and twelfth day, in old times. On New Year's

Eve especially, young women went from house to

* Selden,

Not. on Drayt. Pokolb. IX.

THE HISTORY OF TOASTING.

81

house in their several parishes

carrying the Wassail

Bowl, (called also lamb's wool), made of ale, nutmeg,

sugar, toast, and roasted crabs or apples. At each

house they sang couplets of homely verses, presented

the drink to the inmate3 whom they favoured, and

expected a gratuity in return. Selden alludes to this

custom:— " The Pope, in sending reliques to Princes,

does as wenches do by their

wassails at New Year's

tide ; they present you with a cup, and you must

drink of a slabby stuff; but the meaning is, you must

give them monies ten times more than it is worth."*

It was the custom, too, for the head of the house to

gather the family around a bowl of spiced ale, from

which he

drank their healths. Then he passed it round*

saying wass kaeL

In the Antiquarian Repertory! is a

woodcut of a

large oak beam which once supported a chimney-piece,

on which is carved a large bowl with the inscription—

wass heil. In this spicy bowl, (which, the writer takes

occasion to note, testifies the goodness of their hearts)

they drowned every former animosity; an example, he

thinks, worthy of imitation. The custom was kept up

throughout the middle ages, both in the monasteries

and in private houses. In front of the Abbot wa3 set

the huge cup called

Poculum Caritatis; from it he

drank to everybody, and all drank to each other. In

*

TahU Talk, Art. Pope.

t Vol. I, p. 218,

82

THE HISTORY OF TOASTING.

a collection of ordinances for the regulation of

the

royal household, in the reign of Henry VII., on

Twelfth Night, the steward was told when he entered

with the spiced and smoking drink, to cry "Wassail"

three times, to which the Royal Chaplain had to

answer with a song. Till a very few years ago in

Scotland, the custom of the wassail bowl at the end

of the old year wras kept up. Towards midnight, was

got ready a flagon of warm spiced and sweetened ale,

with a trifle of spirit. As old year glided into new,

each member of the family drank from this flagon " «*

good health and a happy new year, and many of them "

to all the rest, with the addition of a song to the tune

of Hey tuttie taitie :

" Weel may we a' be,

111 may we never see,

Here's to the king

And the gude companie !"#

Warton says that the " Gossip's Bowl" in the

Midsummer JSigMs Dream is the same as the

wassail.

The following are examples of Wassailing songs:—.

" Wassail! Wassail! over the town,

Our toast it is white, our ale it is brown :

Our bowl it is made of the mapliu tree,

Wo be good fellowrs all; I drink to thee."

* Chambers'

Booh of Days. Cf. Strutt's

Sports and Pastimes, B. IV.

e. 3. Brand, Popul. Antiq, Append.

THE HISTORY OF TOASTING.

88

u Here's to---------and his

right ear,

God send our maister a Happy New Year;

A Happy New Year as e'er he did see—

With my wassailing howl I drink to thee."

4i Here's to---------and to

his right eye,

God send our mistress a good Christmas pie:

A good Christmas pie as e'er I did see—

With my wassailing bowl I drink to thee."

The following is from Ritson's Ancient

Songs—

' " Jolly Wassail Bowl,

A wassail of good ale,

Well fare the butler's soul,

That setteth this to sale—

Our jolly wassail."

" Good dame, here at your door

Our wassail we begin,

We are all maidens poor,

We now pray let us in,

With our wassail," &c, &c.

One of the earliest wassail songs is

that introduced

by Dissimulation, disguised as a religious person, in

Bale's old play of Kynge Johan, about the middle of

the sixteenth century. He brings in the cup by which

the King is poisoned, stating that it " passith malme-

54

THE HISTORY OF TOASTING.

saye, capryck, tyre, or ypocras," and

then sings—

11 Wassayle, wassayle out of the

mylke payle,

Wassayle, wassayle as white as my nayle,

Wassayle, wassayle in snowe, froste, and hayle,

Wassayle, wassayle with partriche and rayle,

Wassayle, wassayle that much doth avayle,

Wassayle, wassayle that never wylle fayle."

In Caxton's Chronicle the account of

the death of

King John represents the cup to have been filled with

good ale; and the monk bearing it, knelt down, say-

ing, " Syr, wassayll for euer the dayes so all lyf dronke

ye of so good a cuppe."

In the reign of Charles I. the wassail

bowl was still

in fashion. A few years after, all was changed. John

Taylor, the water poet, complains, " All the harmless

sports, the merry gambols, dances, and friscols .. . are

now extinct and put out of use .. . madness hath

extended itself to the very vegetables ; the senseless

trees, herbs, and weeds are in a profane estimation

amongst them—holly, ivy, mistletoe, rosemary, bays,

are accounted ungodly branches of superstition for your

entertainment. And to roast a sirloin of beef, to

touch a collar of brawn, to take a pie, to put a plum

in the pottage pot, to burn a grep,t candle, or to lay

one block more in the fire for your sake, Master

Christmas, is enough to make a man be suspected and

taken for a Christian, for which he shall be appre^

THE HISTORY OF TOASTING.

$$

hended for committing high Parliament

Treason."

Wassailing fruit trees on the eve of the Twelfth-

day was a curious custom. The Devonshire farmers

used to proceed to their orchards in the eveningr

together with their farm servants, and carry with them

a large pail full of cider, and roasted apples hissing

therein. They then encircled the most fruitful tree

and drank the following

toast three times. The rest

of the contents were then thrown against the other

trees, as a pledge of a fruitful year.

" Here's to thee, old apple-tree,

Whence thou may'st bud, and thou may'st blow !

And whence thou may'st bear apples enow !

Hats full! caps fall!

Bushel—bushel—sacks full!

And my pockets full too ! Huzza !"

The Christmas Poems of Robert Herrick

form a

series of themselves. Some are devoted to the Wassail.

One, entitled

6i The Wassail Bowl," addressed to his

friend John Wickes, is noticeable in this connection ;

in which occur the lines :—

" We still sit up,

Sphering about the Wassail cup

To all those times

Which gave me honour for my rhymes."*

* Robert Herrick was born in London, 1591,

graduated at Cam-;

bridge, after which, he spent aome years in London, counting among

36

THE HISTORY OF TOASTING.

Mr. Blackwell states that before the

introduction of

Christianity the Scandinavians used to meet in select

parties for the purpose of feasting and drinking—used,

in fact, to have regular

drinking bouts, at which he

who drank the deepest or emptied the largest horn at

a single draught was regarded as the hero of the fes-

tival. They were too fond of their ale and mead to

abandon this custom when they became Christians ;

but, as drinking gave rise to quarrels which generally

ended in bloodshed, these private meetings were?

through the influence of the clergy, gradually changed

into public confraternities or guilds, the members of

which, or guild-brethren, as they were called,

pledged

themselves to keep the peace and check intemperance.

The guilds established by the Norwegian King Olaf,

Olaf the Quiet, appear to have been of this descrip-

tion—convivial clubs, in fact, at which " some hilarious

bishop or high dignity of the Church could preside at

his friends Ben Jonson, Selden, Lawes and other

celebrities. In the

year 1629, he was presented to the living of Dean Priors, in Devon-

shire. There he remained for nearly twenty'years, till ejected from

his living on account of his Royalist opinions. On leaving his parish,

deeply regretted by his parishioners who called him their " ancient

and famous poet," he returned to London. His old friends had died.

He soon made new ones; among these were Robert Cotton and Sir

John Denham. At the restoration of Charles II. he was again

admitted to his living, and died Oct, 15, 1674, at the age of eighty-

three. A monument was erected some few years back in Dean

Prior's Church to his memory, by a descendant of the family, the

late and deeply revered William Perry-Herrick, Esq., of Beaumanor

Park, Leicestershire.

THE HISTORY OP TOASTING.

87

the social board, and empty his cup in

honour of the

patron saint of the guild, without in any way infring-

ing the decorum of his sacred office." In the latter

half of the twelfth century these guilds had become

powerful and influential corporate bodies, and the

guild brethren

pledged each other at their convivial

gatherings to afford mutual aid and protection,especially

in judicial affairs. Blackwell thinks that the various

Worshipful Companies of the City of London are

lineal descendants from the old

drinking bouts of the

Scandinavians ; and certainly the immemorial custom

of the loving-cup, still observed at the City dinners,

lends weight to this opinion.

One point of resemblance between the

Northern and

Scandinavian and the Greek and Roman mythologies

is specially worthy of being pointed out,

i.e., the idea

of a future state of bliss being associated with constant

drinking of huge draughts of mead or wine, and much

intoxication. Thus in the Prose Edda we find Gangler

enquiring of Har what the heroes in Valhalla have to

drink, " or do they only drink water ■?" to which Har

replies, "A very silly question is that, dost thou

imagine that Alfadir would invite Kings and Earls

and other mighty men, and give them to drink nothing

but water ? By my troth, they who had endured great

hardships, and suffered pain and wounds even unto

death, in order to gain Valhalla, would think they had

paid too great a price if they only got water-drink.

;S8

THE HISTORY OF TOASTING.

But listen: From the she-goat Laerath,

flows mead in

such abundance that every day she fills a stoop which

is so large that all the champions are fall drunken

out of it" And when Gangler asks what are the

amusements of the heroes who have joined Valhalla,

he is told, " Every day as soon as they have dressed

themselves, they ride out into the field, and there fight

till they cut each other in pieces. This is their pas-

time, but when meal-tide approaches,

* From the fray they then ride,

And drink ale with the CEsir.'"

And in the Voluspa of Scemund we read

that in

Okulni stands a palace called Brimir, " the ale-cellars

of the Jotun;" and again in the Edda of Snorre, how

Thor, in the land of the giants, essayed to empty at

one draught the mighty drinking horn which was kept

at the Court of Utgard-Loki, and which anyone who

wished to regain favour after offence was obliged to

drink from. These instances will be sufficient to show

that the old Scandinavians held drinking in as high

esteem, as honourable, and as essential to a state of

future bliss as did the ancient Greeks.

After the Scandinavian sacrifices,

Snorre alleges

that the ancient Northerners used to hold solemn

feasts, when they drank a cup in honour of Alfadir,

known as

OdirCs cup, in order that they might be

victorious in battles, and that the annals of the reign

THE HISTORY OP TOASTING.

89

might be glorious ; after this they

quaffed cups of ale

or mead to Njord and Frey for a plentiful season"; and

amongst others the cup of the god of poetry and elo-

quence was not forgotten. They also drank to their

heroes, and to such of their comrades as had fallen in

battle, and thus earned a title to live in Valhalla.

The Scandinavians were so addicted to these customs

that the early Christian Missionaries were utterly

unable to abolish them, and so for many centuries the

custom of drinking healths to the Almighty and the

angelic host, was maintained and observed in the

North of Europe.

From Tacitus we learn that the ancient

Germans

passed their time, when not fighting, in feasting and

sleeping, and that the most usual way for a chief to

collect and keep round him a large following of re-

tainers, was by giving magnificent entertainments. It

was at their banquets that the Germans consulted

together on the most important occasions, such as the

election of their princes, making war, and concluding

peace. Mallet says that the ordinary liquors drunk

at these bouts were beer and mead, or when they could

get it, wine, which they drank out of earthen or

wooden pitchers, or from the horns of wild bulls. The

principal person at the table, taking a cup of wine and

rising in his place, saluted by name either the person

next to him, or the one next to him in rank, and then

drank the draught. Having caused the cup to be

40

THE HISTORY OF TOASTING.

re-filled, he handed it to the one whom

he had saluted';

this person then had to drink off the cup.* This

description differs hafdly at all from the practice

adopted to this day at many social and convivial

meetings. Mallet says that it was at these ancient

feasts that those associations were formed of which

the chief tie was a solemn obligation entered into by

each person to defend and protect his companions at

all risks, and to avenge their deaths at the hazard of

their own lives. This oath was taken and

renewed at

their festivals.

From the romance of "Beowulf," a Saxon

poem of

about the middle of the fifth century, supposed to be

a description of events occurring in the Saxon's own

country, but which, from internal evidence, shows the

writer to have been acquainted with Roman architec-

ture, we learn how " it came to the mind of Hrothgar

to build a great mead hall, which was to be the chief

palace." The Queen Wealtheow entered, and served

out wine, first offering the cup to her Lord and Master,

and afterwards to the guests, of whom one was called

Beowulf, This Beowulf had come to free Hrothgar'a

kingdom from a fearful dragon-monster, which the

day after the banquet he succeeded in slaying. To

celebrate this event another entertainment followed

and after dinner a minstrel "again took the harp, the

* Northern Antiquities.

THE HISTOBY OP TOASTING.

41

lay was sung ' the song of the

gleemen,' the joke arose

again, the noise from the benches grew loud," cup-

bearers poured wine from wondrous vessels, and the

queen, under a golden crown, again served the cup to

Hrothgar and the hero Beowulf.

The Saxons were great people for

drinking-vessels.

That they were in the habit of drinking to the health

and memory of the living and dead there is abundant

evidence. Witlaf, King of Mercia, gave the drinking

horn of his table to the Abbey of Orowland, that the

elder monks might drink from it on festivals, and in

their benedictions remember sometimes the soul of the

donor. The Lady Ethelgiva bequeathed two silver

cups to Ramsey Abbey for the use of the brethren in

the refectory, in order that while drink was served in

them her memory might be more firmly imprinted on

their hearts.* Nor can there be any doubt of the use

to which these cups were put by the monks. S. Boni-

face writes to Archbishop Cuthbert in the eighth

century as follows : " In your dioceses certain Bishops

not only do not hinder drunkenness, but they them-

selves indulge in excess of drink, and force others to

drink till they are intoxicated. This is most certainly

a great crime for a servant of God to do or to have

done, since the ancient canons decree that a bishop or

a priest given to drink should either resiga or be

* Fosbrooke,

British Monachitm.

C

42

THE HISTORY OP TOASTING.

deposed."* S. Gildas decreed that if a

monk through

drinking got thick of speech, so that he could not join

in the Psalmody, he was to be deprived of his supper,

It must not, however, he forgotten that many of the

inmates of the monasteries were laymen. In Strutt's

" Manners and Customs of the English " there are

some interesting plates from old manuscripts illus-

trating Saxon drinking parties. One represents a

group in which the central figure is addressing a

friend on his left, apparently toasting him.

The account generally given of the old

manner of

pledging is this : The person who was going to drink

asked any one of the company that sat next to him

whether he would pledge him, on which, the person

addressed answering that he would, held up his knife

or sword to guard the drinker, for while a man is

drinking, he necessarily is in an unguarded position,

exposed to the treacherous stroke of any sudden or

secret enemy. The idea is founded upon the position

of the parties in the before-mentioned illustration, and

upon the comments of historians on the murder of

King Edward, saint in the calendar of the Church of

England, who, while drinking on horseback at the gate

of Corfe Castle, was stabbed in the back by order of

* Discipline of Drink, p. 77. Sanvuelson,

History of Drink, p. 119.

This author also mentions that in the 9th century the Council of Aix

ordered the abbots to dine in the common refectory with the monks,

to put bounds upon theirjndulgence, ib. p. 132.

THE HISTORY OF TOASTING.

43

Ills stepmother Elfrida, of notorious

depravity. Feel-

ing the assassin's steel, Edward put spurs to his horse,

but fell exhausted after going a little way, and expired

in a neighbouring marsh. It is stated that the

treachery of this crime created a general distrust and

dread throughout the land. No one would drink

without security from the person beside him that he

was safe while in the act of drinking; hence, it is said,

arose the customary expression at table or in com-

pany,-—"I pledge you " when one person invites

another to drink first.*

On such slight evidence, however, we

cannot accept

this as the origin of the custom, though, perhaps it

may have had something to do with, stimulating the

Saxons to keep up the guilds or jnutuaL protection

and benefit societies, records of some of which, held

at Exeter, Cambridge, Dover, Canterbury, ancTLondon,

are still existing.

It is rather to the drinking bouts of

the old Saxons,

resulting, as we have shown, in the establishment of

gilds, or guilds, which were common in Germany and

elsewhere in North Europe long before the assassina*-

tion of Edward, that we must trace the (maintenance

* Brand,

Pop, Antig. gives another

explanation; He says^ "others

affirm the true sense of the word to be this: That if the person drank

unto, was not disposed to drink himself, he would put another for a

pledge to do it for him, otherwise the party who began would take>

it ill."

44

THE HISTOBY OF TOASTING.

of the practice of pledging in drink :

for it is quite

evident that the English guilds (or gilds) were derived

from those of the Continent, and were continued by

the Saxons after their settlement in this country for

similar purposes to those which originally called them

into existence. Indeed, that there was great need for

some sort of mutual protection (if we may take Dr„

Henry's account of the overbearing demeanour of the-

Danes at this time to be accurate) is evident, when we*

read that if an Englishman presumed to drink in the*

presence of a Dane without the latter's express per-

mission, it was esteemed so great a mark of disrespect

that nothing but instant death could expiate it. "Nay,

the English were so intimidated that they would not

adventure to drink, even when they were so invited,

until the Danes had pledged their honour for their

safety, which introduced the custom of pledging one

another." That the Danes were not only cruel, but

treacherous also, we gather from the curious collection

of ancient Danish ballads translated by R. 0. Prior.

In one very old one, a husband, after treacherously

murdering his wife's twelve brothers during their

sieep, and whilst they were his guests, fills a cup with

their blood, which he brings to his wife that she

might pledge him in it. Many years after, the wife,

in retaliation, whilst her husband's relations are visit-

ing him, steals out of bed at dead of night, murders

them all, fills a cup with their gore, refr.rns to her

THE HISTOEY OF TOASTING.

45

husband's chamber, and while he still sleeps

securely,

ties him hand and foot. She then wakes him, and,

alter mockingly asking him to pledge her in the cup

of blood, despatches him. At that moment their baby

in its cradle wakes up and cries out, so the mother,

fearing lest in after life her son should avenge his

father's murder, makes matters safe by quietly dashing

its brains out.

In another ballad from the same collection, we

learn

how one of the ancient kings of Denmark, dancing at

a wake with a fair peasant girl, requested her to sing

to him, which she did in tones so clear and thrilling

that she woke the Queen Sophie, who had retired to

bed. Her Koyal Highness's curiosity being aroused,

she got up, put on her purple mantle, and went out to

see what sort of girl the songstress might be. On

seeing her husband dancing with the peasant girl, the

queen's jealousy was excited, and she thought it " a

monstrous thing, that Signelille " (the peasant girl)

should " dance with Denmark's king." So she in-

structed one of her attendants to bring her "the

richly-moulded horn" filled with wine, ordering an

Edder-corn (poison) to be first dropped in. Then,

when the king asked his royal consort if she would

not dance with him, Queen Sophie replied—

" Before a place in the dance I fill,

Must drink to my health fair Signelille."

46

THE HISTORY OF TOASTING.

Signelille accordingly took the horn,

and though she

14 Drank but a sip to quench

her thirst,

Her guileless heart in her bosom burst."

The custom of the northern people to

drink mead

out of the skull of a fallen enemy is proved by

chronicles to have been in use up to the eleventh

century; and the root-word

skoll may be still traced

to this day in the Highland Scotch

skiel (a tub), and

in the Orkneys, where the same word means a flagon.

When Albin slew Cuminum, he

u carried away his

head, and converted it into a drinking-vessel, which

kind of cup with us is called schala." At the period

of the conspiracy of the Earl of Gowrie, one of the

leaders " did drink his

skoll to my Lord Duke ;" and

Calderwood speaks of drinking the king's

skole, which

meant drinking a cup in honour of him, which should

be drunk standing. The fact of drinking out of the

skull of a slain enemy, and the cups of blood in the

Danish ballad, call to mind the account of Plutarch7

that the Egyptians did not drink or offer wine by way

of supplication to the gods, as other nations did, but

only as it bore a resemblance to their enemy's blood.

The Scandinavians regarded as the highest point of

felicity that they hoped to pbtain hereafter, the drink-

ing mead and ale in the Hall of Odin, out of the

skulls of those they had overpowered. This custom

was adopted by other nations. Mandeville tells that

THE HISTORY OF TOASTING.

47

the old Ghiebres exposed the dead bodies of

their

parents to the fowls of the air, reserving only the

skulls, of which he says, " The son maketh a cuppe,

and therefrom drinketh he with gret devotion." Lord

Byron had a skull mounted into a drinking-cup, and

wrote this inscription on it:—

" Start not, nor deem my spirit fled :

In me behold the only skull

From which, unlike a living head,

Whatever flows is never dull.

" I lived, I loved, I quafiFd like thee :

I died: let earth my bones resign :

Fill up—thou canst not injure me,

The worm hath fouler lips than thine.

11 Better to hold the sparkling

grape,

Than nurse the earthworm's slimy brood;

And circle in the goblet's shape

The drink of gods, than reptile's food.

" Where once my wit, perchance, hath shone,

In aid of others let me shine;

And when, alas ! our brains are gone,

What nobler substitute than wine ?

" Quaff while thou canst, another race

When thou and thine, like me, are sped,

May rescue thee from earth's embrace,

And rhyme and revel with the dead.

48

THE HISTORY OF TOASTING.

" Why not ? since through life's little

day

Our heads such sad effects produce ?

Redeemed from worms and wasting clay,

This chance is theirs—to be of use."

The Saxons, we know, used to cut their foreheads, and

let drops of their blood fall into a cup of wine, which

they then drank to the health of any particular beloved

or esteemed friend. That this custom was remembered

and observed so late as the seventeenth century, is

shown by some lines in the

Oxford Drolleryy in which

is a song containing the following lines :—

" I stab'd mine arm to drink her

health,

The more fool I, the more fool I."

Frequent allusions are also made to

this habit in the

plays of Beaumont and Fletcher, to which we shall

refer in speaking of the practice of the custom in

their time.

We may here mention another custom of

health-

drinking at ancient Danish weddings, referred to iu

another ballad in Mr. Prior's collection,

Knight Sti/s

Wedding, namely, the use of two cups, presumably

one being for the use of the person pledging, and the

other for the use of the person pledged. After the

wedding of Stig, the entire party proceeded to the

large hall to participate in the merry-making, and

" As o'er the floor the dancers sped,

The graceful knight the revellers led ;

THE HISTORY OP TOASTING.

49

Graceful he tripped before the band,

Two silver cups in either hand.

He then to his bride a goblet drained

That aye was best that God ordaiu'd."

In this case it is tolerably certain that the

bride*

groom did not pledge his bride, or vice versa, from any

feeling of insecurity, but merely in compliance with

Mie very old custom of drinking a cup of liquor as a

token of veneration, esteem, or love for anyone.

In connection with drinking healths or toasts at

weddings, it is not out of place to refer to an ancient

Jewish custom, which is still kept up; that of the

bride and bridegroom, immediately after the marriage

ceremony, drinking wine out of the same glass and

then breaking it, the meaning of which, Brand thinks,

is to remind the couple of their mortality ; but a

somewhat analagous observance has been recorded of

lovers drinking solemn toasts to their mistresses and

immediately dashing the goblet down, with a very

•different meaning, which is referred to in some stanzas

of which the first lines run—

11 We break the glass whose sacred

wine

To some beloved name we drain,

Lest future pledges, less divine,

Might e'er the hallowed cup profane."

Nor should we forget a form of health given in

the

life of Wenceslaus. A person taking the cup cried in

00 THE

HISTORY OF TOASTING.

a loud voice, " In the name of the

blessed archangel

St. Michael, let us drink this cup, begging and pray*

ing that he will think worthy to introduce our souls

to eternal happiness. To this the rest answered

'Amen,'" and the toast was drunk. This testimony

of aifection to saints, as well as to the souls of the-

dead is prohibited in councils. Neubrigensis addsr

that it drove away devils, like monkeys, who sat upon

the shoulders of the visitors.*

The ancient Normans, or Northmen, who

from their

own sterile country (Norway) used, before the ninth

century, to make frequent raids upon the more fruitful

countries towards the south, were constantly assisted

in their attacks on the sea-coast of the Netherlands,

England, and France, by the Danes, and in their

manners and customs they closely resembled them as

they did the Saxons; and their language was originally

much the same as the ancient Danish. It is probable

that the superior natural features of that part of

France we now call Normandy, caused them to make

frequent attacks thereon. In order to rid himself of

the trouble of constantly repelling the invaders,

Charles the Bald King of France at last gave the

earldom of Ohartres to one of the leaders of the

Northmen, by name Hastings or Harding. Subse*

quently Charles the Simple confirmed this grant upon

*■ Fosb.

Cycl. Ant. II. 600.

THE HISTORY OF TOASTING.

51

Hastings' descendant Rollo, though not

until that

rover had annexed a considerable part of Normandy.

Daring the time that elapsed between this and the

invasion of England by William the Conqueror, the

Normans lost their own tongue and acquired that of

the French ; and out-stripped in civilization their

cousins the Anglo-Saxons and Danes lately settled

in England.

Without trespassing upon irrelevant

matter it is to

be observed that the use of wine amongst the ancient

Normans in many respects closely reflected the cus-

toms of the Saxons and Danes. They indulged in

wine; the clergy especially. And as the ceremonial

observances in drinking were unchanged, so likewise.

was the excess.

Reginald of Durham, the story-writer of

the twelfth

century, in one of his tales makes a party in a private

house sit round the fire and drink together sociably;.

in another he gathers at the house of the parish priest

of Kellow a number of the villagers, who with their

spiritual pastor spent the greater part of the night in

drinking; again we are introduced to a youth who

goes, accompanied by his tutor (a monk), to a tavern,

where they spend the whole evening in drinking, til^

one of them gets so intoxicated that he absolutely

refuses to go home.

These tales of Reginald are undoubtedly

faithful

representations of the manners of that day ; and that

52

THE HISTOBY OF TOASTING.

the clergy of that time were in the

habit of unduly

carousing is quite evident from the canon of Arch-

bishop Anselm, made at the Council in London in

1102, whereby priests are enjoined not to go to

drinking bouts, nor to drink between pins. There is

not the slightest doubt that health-drinking was an

important feature at these drinking bouts, and that

the intemperance thereat was so great as to be a

scandal, not only to the people but to the clergy, who

instead of trying to put down the evil, on the contrary

participated in it.

Excess in ale-drinking had prevailed to

such an

extent in Dunstan's time, and was productive of so

many quarrels, that he was obliged to propound a

law for the regulation and restriction of alehouses,

and also caused the drinking-vessels used at such

places to be furnished with gold or silver pins or pegs

fixed at regular intervals inside, so that when two or

more drank in company out of the same measure, each

might know what was his fair share of the liquor.

CHAPTER IV.

Toasting froh the Twelfth to the

Sixteenth

Century.

At a Lateran Council held in Innocent

III.'s popedom,

the following decree was published:—" Let all clergy-

men diligently abstain from surfeiting and drunken-

ness; for which let them moderate wine from themselves,

and themselves from wine 5 neither let anyone be urged

to drink, since drunkenness doth banish wit and pro-

voke lust. For which purpose we decree that that

abuse shall be utterly abolished, whereby in divers

quarters drinkers do use after their manner to bind

one another to drink equally, and he is most applauded

who makes most people drunk and quaffs off most

carouses. If any offend henceforth in this respect,

let him be suspended from his benefice."

And at the Council of Cologne in 1536 a

decree was

passed to restrain the Popish laity, parish priests, and

clergy from the baleful practices of drinking healths ;

so that down to that date it does not seem that there

had been any diminution of the drunkenness attendant

upon the unbridled wine and beer-bibbing induced by

the custom of toasting, pledging, and health-drinking,

£-k

THE HIST0EY OF TOASTING.

which Greeks, Romans, and Scandinavians

had alike,

and independently, indulged in before the Christian

era, and which had been from them transmitted with

scarce any alteration of form or manner to later

generations.

Nearly every monastery in France had

its vineyard,

whereas the ordinary drink of the Anglo-Saxons was

ale and mead, though they sometimes drank wine.

The vine was cultivated in England from the time of

the Roman Emperor Probus, who permitted the plant-

ing of vineyards in this country, both for use and for

pleasure, though most of the wine consumed here was

imported from the Continent. In an early illuminated

Anglo-Saxon calendar are pictorial illustrations of the

seasons, in some of which husbandmen are depicted

pruning and cultivating vines. William of Malmes-

bury praises the Gloucestershire vines, and says that

the wine made from those grapes was but little

inferior to that imported from France. The same

writer tells us that the monks of Glastonbury had,

on special occasions,

u mead in their cans, and wine

in their grace-cup."

The social life of monks has been

reprobated and

in turn defended by historians. Their capacity for

unlimited potations has been cleverly satirized in the

lines—

•• 0 monachi, vestri stomachi sunt

amphora Bacchi,

Tos cstis, Deus est testis, teterrima pestis."

THE HISTORY OF TOASTING.

55

Nor has the imputation been veiled in

the following

rendering—

" 0 monks, ye reverend drones, your

guts

Of wine are but so many buts ;

You are, God knows (who can abide ye ?)

Of plagues the rankest,

bonajide."

Eabelais seems to have thought better

of them in the

lines—

" The Devil was siek, the Devil a monk

would be ;

The Devil was well, the Devil a monk was be."

It is certain that they enjoined

temperance—

" Nee gulosus

In Siversis epulis,

Nee in potu vinolentus."

" Nor dainty in your various meals,

Nor vinolent in drink."*

But whatever their precept their

practise was

undoubtedly censurable too often, hence such satires

as were commonly in vogue. We read of an Abbot

who in order to exhilarate a certain knight, plied him

with choice liquor, in the English fashion. In order

to provoke him to drink more heavily, instead of

was-

• cf. Fabriciufl " Biblioth Med. MU VII. 913.

56

THE HIST0BY OF TOASTING.

heilj the Abbot gave for the

toast the word Pril, to /

which the other was enjoined by the Abbot, instead

of

Drink-heil to reply Wril; and thus drinking and

toasting with

Pril and Wril, and assisted by the

monks, lay brothers, and servants, they went on till

midnight.*

The grace-cup is so intimately

connected with the

custom of health-drinking, pledging and toasting

that some account of it will not be out of place. It

is supposed to be a perpetuation of the

cup of thanks-

giving of the early Jews, alleged to have been taken

by Abraham; and the same as the

cup of salvation

referred to in Psalm cxvi. 13. The cup of undiluted

wine which the Greeks passed round at their feastsr

drinking to the good spirit, and the poculum boni genii

of the Romans, had their origin probably in the

Jewish custom. The cup and its custom were retained

after the introduction of Christianity ; whether, how-

ever, the English name

grace-cup is derived from the

Latin word gratias, or from the fact that it is passed

round immediately after meals at

grace time, is Or

moot point. It is unnecessary to go

into minute

details about the observances connected with drinking

the grace-cup; it will be sufficient to remark that

nearly every religious body, and subsequently nearly

every public corporation, had one of these vessels,

♦ M.S. Cott. Tiber B. B, 13. Cited by

FoaJ>roke.

THE HIST0KY OF TOASTING.

57

which they used with much solemnity on

certain

occasions ; and that in some cases bastard customs

sprang therefrom, as for instance the

Agapce, which

Aubrey says were <6 certain love feasts used in thd

Primitive Church, where all the congregations met

and feasted together after they had received the Holy

Communion, and those that were rich brought for

themselves and the poor, and all ate together for the

increase of mutual love, and for the rich to shew their

kindly charity to the poor." This explanation is given

in connection with an account of a custom observed

by the inhabitants of Danby Wisk, a village in the

North Riding of Yorkshire, where the parishioners

used every Sunday after receiving the Sacrament to go

straight from the church to the ale-house, and there

drink together in testimony of charity and friendship.

There does not seem to have been much difference

between the grace-cup

(poculum caritatis), the wassail-

bowl, and the loving-cup, which still circulates at the

public entertainments of various public bodies. la

fact, the loving-cup now in possession of the Lichfield

Corporation was at one time called

poculum caritatis,

the history of which is interesting. In 1633, one

Elias Ashmole, a wealthy man, and a native of

Lichfield, presented to the bailiffs of his birthplace

a large chased silver drinking bowl and cover, which

had cost him £23 8s. 6d. From that time till the

present day the ceremony of drinking from it with all

s>

58

THE HISTORY OF TOASTING.

all pomp and formality has been duly

observed at the

corporation feasts and city banquets. On these occa-

sions the mayor always drinks first. In his place at

the head of the table he stands up and takes the cup

in both hands. The person next him on his right

hand and on his left rise also. After drinking he

hands the cup to his right-hand neighbour, when the

person on this one's right rises ; then the cup is passed

across the table to the Mayor's left hand neighbour,

when the person on his left hand rises ; and so on till

the cup is emptied or all have drunk from it, it being

always arranged that the person drinking should have

the person next to him and the one opposite to him

standing while he drinks. In the letter from the

Corporation, thanking Mr. Ashmole for his present, is

the following passage :—u Upon the receipt of your

Poculum Ckaritatis.....we filled

it with

Catholic Wine, and devoted it to a

sober Health to

our most Gracious King, which, being of so large a

continent, passed the hands of thirty to pledge. Nor

did we forget the health of yourself in the next place,

being our great Mecaenas." Nor, in speaking of

grace-cups, should we omit to mention the Durham

Prebend's cup, which is drunk at certain feasts which

the resident Prebendary gives to the City Corporation

and inhabitants, and for which he is, in virtue of

an old charter, allowed a liberal annual sum. The

composition which is drunk on these festive occasions

THE HISTORY OF TOASTING.

59

is brewed from a very ancient recipe,

and it is served

in the original silver cups, which hold two or three

quarts, and are at least a foot high. A chorister boy

in a black gown, preceded by a verger in a silver-

braided black gown, carries the cups into the ban-

queting-room. A Latin grace is then chanted, the

Prebend gives the boy a shilling, and then verger and

cup-bearer march out of the room, leaving the filled

cups on the table. These are then passed down, one

on each side, and are drunk by each guest in succession

to an appropriate toast. It does not seem that there

was so much formality at Durham as at Lichfield in

the ceremony of drinking, but at Westminster, at the

churchwardens' dinners and parish meetings of St.

Margaret's, the strictest attention was paid to every

detail of formality, which was much the same as at

Lichfield, only that there were always three persons

standing at the same time on the drinker's side of the

table, one on either side of him, who, while he drank the

toast, held over his head the lid of the drinking-vessel.

Mr. Wright* quotes from a thirteenth century ballad

in which is described the hospitality of a feudal castle

offered to a passing knight, how after dinner the party

washed their hands and then drank round, thus :

" Ses mains

Lava et puis l'autre gent toute

Et puis se burent tout a route :"

* " Homes of other Days."

60

THE HISTORY OP TOASTING.

a proceeding evidently resembling very

closely the-

later age practice of Eotcnds of Toasts, and health-

drinking by people who prided themselves on their

polished civilization. In Edward IV.'s reign, drunk-

enness was such a fruitful source of crime that very

few places were allowed more than two taverns, and

in London itself there were only forty. None but

those who could spend 100 marks a year, or the son of

a Duke, Marquess, Earl, or Baron, were allowed to

keep more than 10 gallons of wine at once ; and only

High Sheriffs, Magistrates of cities, and inhabitants

of fortified towns, might keep vessels of wine for their

own use.

During the thirteenth, fourteenth, and

fifteenth

centuries, though we have no detailed descriptions by

writers of that period of the manners and customs of

the people, there are scattered, through ballads and

romances, allusions which have enabled such inde-

fatigable antiquarians as Mr. Wright to furnish us

with tolerably complete pictures of the domestic life